Julia Henshaw in West Kootenay

- Greg Nesteroff

- Jul 5, 2018

- 5 min read

Updated: Sep 8, 2025

Michael Kluckner’s new graphic novel, Julia, is a biography of Vancouver’s Julia

Henshaw (1869-1937). She was, among other things, a music and drama critic, columnist, novelist, socialite, botanist, fellow of the Royal Geographical Society, ambulance driver, and recipient of the Croix de Guerre.

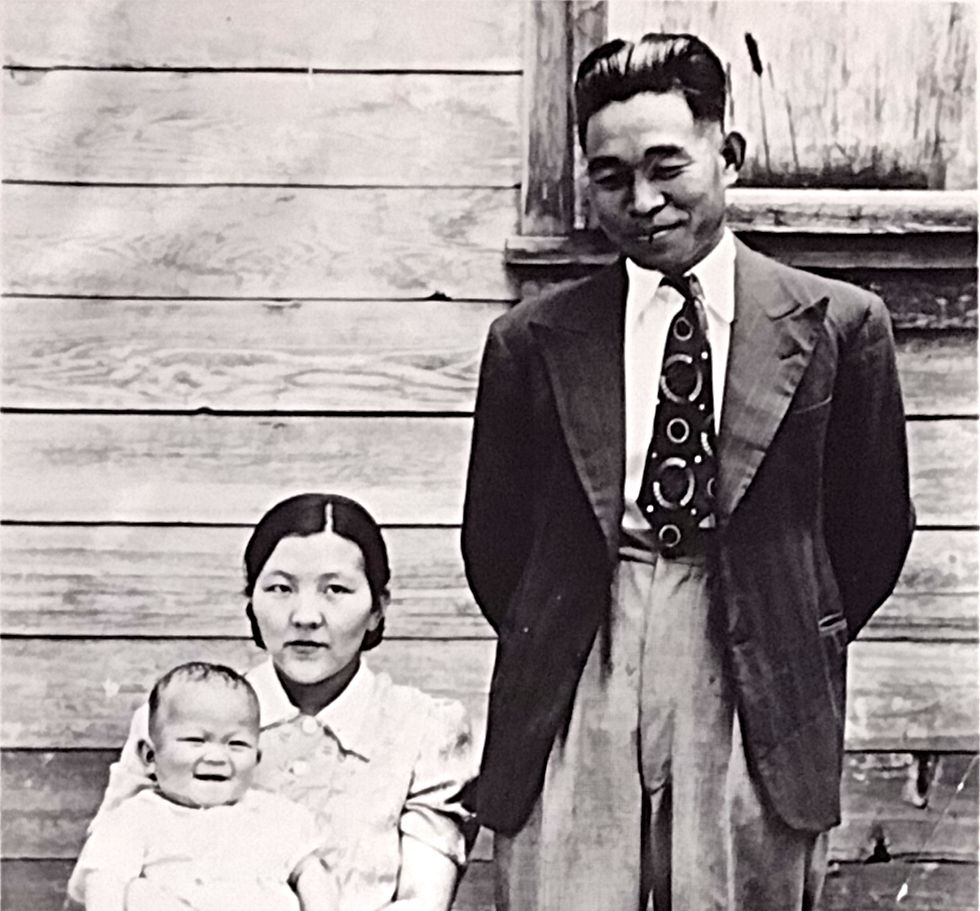

Henshaw (pictured here ca. 1920, in a photo from Wikipedia) visited the West Kootenay in 1898 as part of a tour for the Vancouver Province that also inspired a novel. It forms an interesting part of Kluckner’s book.

The Sandon Mining Review of Sept. 3, 1898 noted a Mr. and Mrs. Henshaw of Vancouver staying at the Reco Hotel — presumably her, but I can’t be certain. (The book portrays them outside the Sandon Hotel.)

If it was her, she returned a few months later, as the New Denver Ledge of Nov. 24, 1898 reported under the headline “A Talented Authoress”:

Mrs. Henshaw, of Vancouver, known to the literary world as Julian Durham, and a sister of Mrs. Chas. Loewen, of the Alamo Concentrator, is obtaining considerable fame as an authoress. For years she has been a regular newspaper writer, her musical criticisms in the Province especially calling forth much attention. She has recently published a novel, called Hypnotized, and it is highly spoken of by literary critics, who predict for Mrs. Henshaw a successful career.

The Ledge erred in describing Mrs. Loewen, the former Edith Falk, as Julia’s sister. They knew each other, but weren’t related. Charles was a Vancouver realtor and mining broker who in 1894 sold lots at Three Forks, a community that thrived for a few years, then went into a slow, steady decline. It’s now a ghost town, as is Alamo.

The results of Julia’s tour appeared in print near the end of the year and the Sandon and New Denver portions were reprinted in the Ledge and Sandon Paystreak. You can read the whole thing here and here, but this is her take on a vertigo-inducing part of the Kaslo and Slocan Railway:

Thus we approach the celebrated Payne Bluff where the train follows an acute angle across alternate rockspurs, which drop away from the railway track to the creek’s edge. It is a sight unparalleled anywhere in the world, for during the moments that it takes to round the point, the cars with their human freight are literally suspended out in mid-air, on a scaffolding pinned to the face of the Payne Bluff itself at the giddy altitude of 1,050 feet. Almost before you can realize the awful chasm that yawns beneath your feet, the sickening sensation is past, and in a short while the train steams into Sandon …

Her portrayal of the area irritated the Mining Review, which wrote on Dec. 31, 1898:

If Mrs. C. Henshawe’s [sic] book Hypnotism is no more reliable than her description of Sandon is accurate, all we have to say is God help the readers thereof. In her description of this place she says the sun does not shine on it for three moths [sic] at a time, when every resident knows there knows there is not more than a month at this time of the year when Sol cannot be seen by residents every day. She says too there is but the one street in the place, when even a drunken man could find two parallel, and several cross streets. But here is a posy from her pen: “The actual level ground in the valley covers an area scarcely 20 feet in width,” when the distance from the K&S depot to the south of the CPR where the old depot stood, which is a stretch of fairly level ground, cannot be much less than one-eight [sic] of a mile. In a short time Sandon will have two very well-graded streets, with good buildings on both sides of one, at least — as it has to a certain extent at present — and they several rods apart, the vision of Mrs. Henshawe nevertheless to the contrary.

Despite the Mining Review’s protests, her less-than-flattering assessment was closer to truth than fiction.

Julia’s journey also took her to Rossland, but I haven’t read what she wrote about that city. The Rossland Miner of Aug. 27, 1898 noted her visit:

Mr. and Mrs. Henshaw of Vancouver are spending a few days in camp. Mrs. Henshaw is preparing a series of articles descriptive of British Columbia life for a syndicate of English periodicals, and will devote a separate article to Rossland. Mrs. Henshaw displays such a keen interest in her work that it is safe to say that her letters will be very interesting.

The next day the Miner added: “Mr. and Mrs. Henshaw, correspondents of London periodicals, left last evening for Trail, where they will look over the big smelter.”

The trip helped inform two key portions of the novel Why Not Sweetheart, published in 1901, which Kluckner illustrates. One chapter takes place on Payne Bluff, where heroines Agnes and Naomi go for a stroll. Some of the description comes straight from Julia’s travelogue.

As they again approached the Bluff, a terrific precipice, past which the track runs on alternate rock-spurs and wooden trestles, built out from the face of the cliff over a thousand feet up in the air, the girls looked down between the ‘ties’ into space, and their brains fairly reeled at the awful chasm that yawned beneath the rails. Suddenly with a spasm of fear Naomi clutched her companion’s arm.

‘The train!’ she gasped.

Although neither ends up tied to the track, there is a mustache-twirling villain named Professor Panhandle, whom Kluckner depicts as Snidely Whiplash of Rocky and Bullwinkle fame.

The climax takes place in Rossland, where the villain sends Naomi’s beau plunging down a mining tramway in a runaway bucket and then struggles with another character on top of a cliff.

The Nelson Economist of Nov. 13, 1901 noted the character of Joseph Kingsearl, MLA for the fictional constituency of Illecillewaet, shared his initials with James Kellie, the MLA whose riding actually included Illecillewaet — but “so far as has been given to the public to know, Mr. Kellie has never been the hero of so many hairbreadth escapes … Nor yet would he be chosen offhand as a hero of romance.”

Furthermore, “if any of the murders recorded in the novel ever took place in Rossland camp, the details have so far eluded the vigilance of the Rossland Miner.”

Still, the Economist concluded that Why Not Sweetheart was “a very attractive novel and one that will well repay perusal.”

By contrast, the Sandon Paystreak of Nov. 15, 1902 could not hide its lingering enmity over her travelogue of 1898: “Mrs. Henshaw of New Westminster will rite [sic] a book, the scene of which is laid in Kootenay. The Paystreak cannot see what the residents of Kootenay have done to Mrs. Henshaw to call for this libel.”

(Were they unaware she had already written such a book or was she planning another? It’s unclear.)

You can read the first 19 pages of the novel online here for free, but the rest requires a subscription.

Julia Henshaw returned to the area in 1917, speaking on “The Fields of France” at a fundraiser in Kaslo for the Red Cross.

Updated Nov. 9, 2018 with quotes from the Rossland Miner and on June 2, 2024 to add her 1917 return.

—————————

For more on Sandon, check out my new book at kingofsandon.com

Comments