Not many reminders remain of Sandon’s time as a Japanese-Canadian internment camp in 1942-43. I’ve written about one of them before, a concrete slab near the cemetery with Ken Sato’s name on it.

Two others can be found in — and on — the museum. A metal stand attached to the Reco Hotel guest book bears the following names:

Misae Jean and Kikuye Kay Akada were sisters and worked in the Reco Hotel during the internment. Kay lived in Toronto from the late 1940s until her death in 2018. She married Shori Kiyonaga and had three children. According to her daughter, Elaine Taylor, she ran a snack bar in the west end of Toronto with her sisters and was well known for her pies and engaging personality. Misae married Ken Hatanaka and had two sons. She too lived in Toronto until her passing in the 1990s.

From ancestry.com, we learn that Isamu (Sam) Kondo was the son of Denya and Kiku (Miyauchi) Kondo. By 1951 he was living in Hamilton, where he married Marge Nishimura and they had at least one daughter, Patricia. However, the date of his death is unknown.

Mitsugi Araki was born in Cumberland to Manzo and Naktku Araki. There’s a photo of his Sunday school class in the 1930s here. He was a baseball player, noted in The New Canadian of July 14, 1945 as playing for Summerland. He died in Kelowna in 1989, age 67, survived by his wife Yoneko. At the time he was a retired miner living in Peachland.

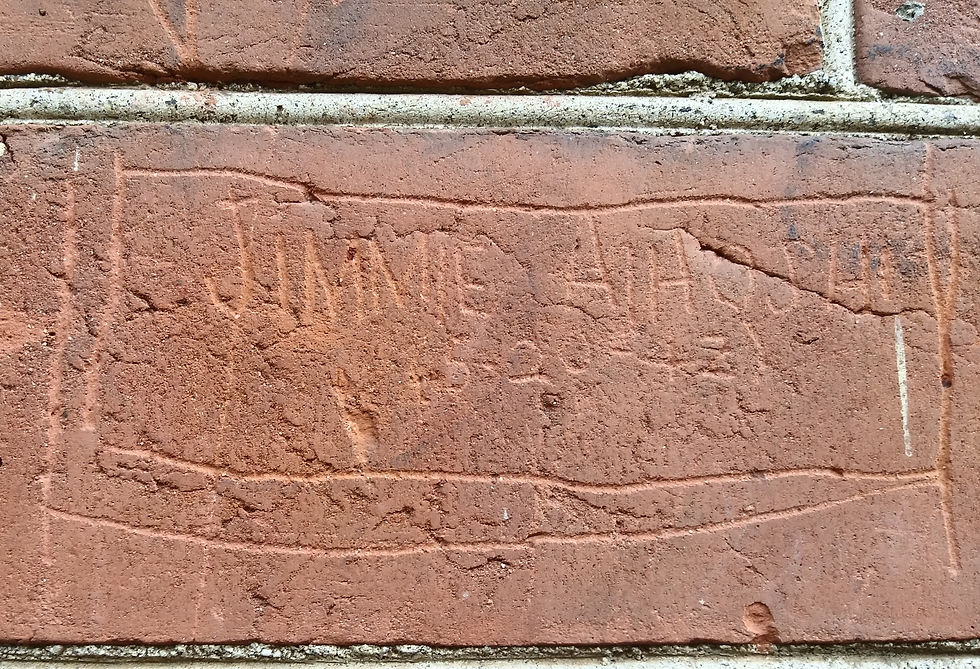

Several names are also scratched into bricks on the museum’s exterior, although most are illegible. I had never noticed them in all the times I have visited Sandon until my mother-in-law pointed them out last year. (This building is the former Slocan Mercantile and was leased to the BC Security Commission during the internment by John Morgan Harris, who owned much of the town.)

The date on the last one — Aug. 9, 1950 (or Sept. 8, 1950) — is interesting because this was long after Sandon ceased to be an internment camp.

But it’s this one that has the best back story:

It reads “Jimmie Aihoshi 5-20-42.”

When I sent these photos to author-historian Chuck Tasaka, he quickly put me in touch with Jimmie Aihoshi’s daughter Susan, who wrote Torn Apart: The Internment Diary of Mary Kobayashi (2012). It’s a fictional diary of a young girl living in Vancouver when the interment began, based partly on her family’s experiences. Both her mother and father’s families were interned in New Denver.

In 2013, Susan also wrote a series about rediscovering her family history for The Bulletin, a Japanese Canadian journal. You can read part one here, part two here, and part three here.

Susan’s father died when she was a teenager, but she was able to glean information from his brother Barney. In 2009, she and her husband went from Toronto to Red Deer to see him, where he astonished her by revealing that Jimmie was born in Japan — she always believed he was born in Vancouver.

They then headed for the Slocan Valley, and visited the Nikkei Internment Memorial Centre in New Denver; Rosebery (where her mother and aunt once taught school); the Langham Cultural Centre in Kaslo; and Sandon — where her father, uncle, and friends had fixed up old buildings to house Japanese Canadians.

“My uncle told me some unforgettable stories about Sandon and New Denver, some of which appear in Torn Apart,” Susan writes.

However, she didn’t know about the brick with her father’s name on it. She kindly provide me with the biography of her father and pictures seen below.

Jimmie Aihoshi is seen above and below, in his early 20s, ca. 1942-43. The photo below was probably taken in New Denver.

James Naotaka Aihoshi was born on May 24, 1920 in the village of Higashikaseda, Kagoshima, Japan. He immigrated to Canada as an infant in August of that same year, with his mother Nobu. His father, Naosuke (Harry) Aihoshi, became a naturalized Canadian in 1914 and returned to Japan to marry Nobu but raised his large family in Canada.

James (Jimmie) was the oldest of six; his siblings were all born in Vancouver, the city Jimmie always regarded as his hometown. In 1932, Nobu became very ill after the birth of her youngest child and died not long afterwards. Jimmie’s father adopted a young woman from Japan, a distant relative, to help raise the children who came to regard her as a beloved older sister.

After completing his education at Britannia High School in Vancouver’s east end, Jimmie worked at his father’s tailor shop on Main Street and drove the family’s car to make deliveries. After Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor during World War II, increasing restrictions disrupted life for Japanese Canadians in BC.

By early 1942, Jimmie and his brother Barney were forced to join work crews sent to prepare internment camps for displaced Japanese Canadians in so-called ghost towns in BC’s remote interior. The pair ended up in Sandon where they refurbished abandoned buildings later housing some of the nearly 22,000 people ordered to leave their homes on the coast.

Slocan Valley lumber companies were experiencing a wartime labour shortage at the same time as they faced increased demands for their products, being used to construct thousands of shacks in the camps. Jimmie was one of a handful of Japanese Canadians hired to drive a lumber truck. All vehicles owned by Japanese Canadians had been impounded and permission from the RCMP was required to move from camp to camp. Yet somehow Jimmie gave rides in his truck to internees needing transport.

Jimmie Aihoshi in his lumber truck. Location unknown, but probably New Denver.

At the Cape Horn bluffs north of Slocan.

Unknown lumber camp.

The rest of the Aihoshi family was sent to New Denver, where they were reunited with the oldest sons. However, life in the cramped cabins and the remote locale with no future opportunities spurred Jimmie and Barney to leave BC, a decision likely prompted by the federal government’s 1944 edict that Japanese Canadians had to decide between going “back” to Japan or move east of the Rockies.

The pair made it to southwestern Ontario, where they struggled to find meaningful work and accommodation. They eventually landed in what is now known as the Greater Toronto area, where Barney was employed at Woodland Nurseries, owned by the socially enlightened Macklin Hancock. Jimmie found various odd jobs, including driving a delivery truck, but by 1949 he had secured steady work at a dry cleaning establishment.

Above: Overlooking New Denver, probably in the fall of 1942 as the sanitarium had not been built yet. Below: Jimmie Aihoshi walks down Front Street in Kaslo. It’s not known what occasion he was dressed up for. Still standing are Eric’s Meat Market and Willow Home Gallery at far left. The four buildings on the right all burned down in January 1950. The three storey building had the Oddfellows Hall.

He married Marie (Molly) Iwasaki in 1948, and they had two children. Jimmie stayed at the same dry cleaning firm until his premature death from cancer in 1967 at the age of 47. He was a quiet and modest man, well regarded by all who knew him.

During his early days in Toronto, Jimmie became a close friend with Irish immigrant Patrick Gorman, who was best man at Jimmie’s wedding and godfather to daughter Susan. The Aihoshi and Gorman children spent countless time together in each others’ homes, regarding each others’ parents as aunt and uncle, and each other as cousins.

Jimmie loved baseball and was an ardent Brooklyn Dodgers fan. Susan remembers her mother describing how she and Jimmie drove to the United States just to watch Jackie Robinson play. Later Susan recalled how much her dad admired Sandy Koufax, perhaps not only for his pitching prowess but for his refusal to play the first game of the 1965 World Series because it was Yom Kippur.

Jimmie’s oldest sister, Alice, was a volunteer high school teacher of the Japanese Canadian children in New Denver. She passed away just this summer at 96.

— With thanks to Susan Aihoshi, Elaine Taylor, Elizabeth Scarlett (Kootenay Lake Historical Society), and Chuck Tasaka. Updated on Oct. 16, 2020 to add/correct details about Kikuye Kay and Misae Jean Akada.

コメント